Walter Leal: From 'Rough Childhood' to Internationally Recognized Scientist

Featured in American Entomologist

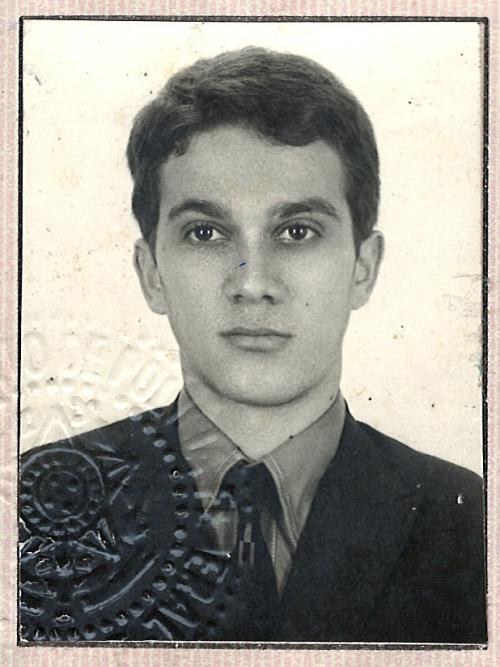

UC Davis distinguished professor Walter Soares Leal soared from a self-described “rough childhood” in his native Brazil to become an internationally recognized scientist celebrated for his research on chemical communication and olfaction in insects.

But in his early childhood, he disliked insects, especially the cockroaches that crawled into his mouth while he was sleeping, and mosquitoes that bit him when he was and wasn’t.

So related Marlin Rice when he chronicled the life of "living legend" Walter Leal in the winter issue of American Entomologist, published by the Entomological Society of America (ESA). Rice, an ESA past president who writes the interview-style Legends column, earlier spotlighted UC Davis entomologists Bruce Hammock, Frank Zalom and Robert E. Page Jr.

The Leal piece, titled “Walter Soares Leal: For the Love of Teaching,” zeroes in on his career accomplishments in Brazil, Japan and the United States, all of which led to his election to the prestigious National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in April of 2024.

Rice interviewed Leal last August in Kyoto at the International Congress of Entomology (ICE 2024), where Leal was chairing the International Congresses of Entomology Council and serving as a volunteer “citizen of the world” ambassador. Leal speaks Portuguese, Japanese and English.

Leal, who joined the UC Davis entomology faculty in 2000, advancing to professor and chair of the department, has served as professor of biochemistry with the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, College of Biological Sciences, since 2013.

Highly honored by his peers, Leal is the only UC Davis faculty member to receive all three of the Academic Senate’s major honors: the 2020 Distinguished Teaching Award for Undergraduate Teaching, the 2022 Distinguished Scholarly Public Service Award, and the 2024 Faculty Distinguished Research Award. His teaching honors also include the 2020 Award for Excellence in Teaching from the Pacific Branch of ESA.

Elevator Bunny on High. “Walter is the elevator bunny on high, a full-time teacher, a full-time scientist, and he is engaged in multiple projects that make the university community a better place, all at the same time,” commented UC Davis distinguished professor and longtime NAS member Bruce Hammock, in a 2024 UC Davis news story announcing Leal’s election to NAS.

Leal holds a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil; a master’s degree in agricultural chemistry from Mie University, Japan; and a doctorate in applied biochemistry from the University of Tsukuba, Japan. He completed a postdoctoral fellowship in entomology and chemical ecology at the National Institute of Sericultural and Entomological Science, Japan.

One of Five Siblings. Walter, the youngest of five siblings, related that his father was a baker and pastor, and his mother, a seamstress. “My dad passed when I was twelve,” Leal said. “It was a hard time in my life. He got sick when I was six and could not do too much…Basically, my mother ran the whole family without any income. But it’s part of my life.”

Neither parent received a high school education, but it was his widowed mother who encouraged him to attend college. “She knew that technical school was not for me…She never went to high school, but she had a vision. Some people have little education, but that doesn’t mean they have no vision.”

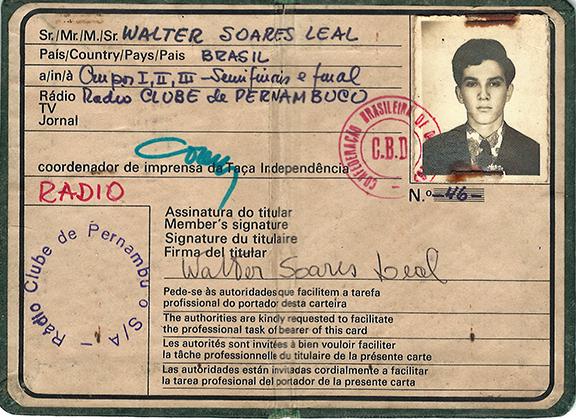

In high school, Walter began earning money--and prestige--as a radio-broadcast journalist, covering soccer and other sports. He went on to cover the USA Open Cup in the United States.

Challenges. Rice began his Legends piece with: “When Walter Leal was offered a scholarship to leave his native Brazil and begin graduate education in Japan, he was required to become proficient in both Japanese and English--two languages he had never spoken--within six months. He accomplished this challenge, eventually earning both his master’s and Ph.D. degrees. He was then offered a research scientist position with the National Institute of Sericultural and Entomological Science in Tsukuba, Japan, eventually becoming head of the Laboratory of Chemical Prospecting for six years. Leal was the first foreigner to be granted tenure at that institution.”

Leal’s research accomplishments, Rice wrote, include “the identification of the first receptor in mosquitoes for the insect repellent DEET; the first isolation, cloning, and expression of pheromone-degrading enzymes in moths; and the identification and synthesis of complex pheromones from many insect species, including scarab beetles, true bugs, longhorned beetles, citrus leaf miner, navel orangeworm, citrus fruit borer, and many others. Synthetic sex pheromones for some of these pests are now being deployed via mating disruption in projects that have saved producers in Brazil and California hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Among Leal’s scores of accomplishments: he co-chaired the 2016 International Congress of Entomology in Orlando, Fla., a conference that drew 6,682 registrants from 102 countries. He is a Fellow of ESA (2009), Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (2005), Fellow of the National Academy of Inventors (2019), and a trustee of the Royal Entomological Society (2024).

Some excerpts from the interview:

Rice: “You are a biochemist without a single entomology degree, yet you have been honored by numerous entomological societies that recognize your talents in insect research.”

Leal: “This is exactly what I said in my opening remarks as chair for the International Congresses of Entomology. My point was that entomologists are such an open-minded people that they welcome anyone who has anything to do with entomology. If you are a high school student doing entomology, we consider you an entomologist. But if I were a medical doctor, I would be arrested for practice without a license ( laughs ), but entomology, on the contrary—all these major societies, they welcome and honor me. They see me doing something for the advancement of entomology. When I started research on these scarab beetles and pheromones, I didn’t come from entomology. I had to learn a lot. But then you contribute to the science of entomology; that’s how entomology sees things. This is the best profession that welcomes everyone without the training. You don’t need a degree in entomology to be an entomologist.”

Rice: “When someone who is not a scientist asks what you do, what do you tell them?”

Leal: “I tell them I am an entomologist, and I try to talk a little bit about mosquitoes because that is something everyone understands. I explain that I look at how they smell things, and that I exploit that in order to generate new compounds or new things that might be useful. If they ask what I do, I tell them I work at UC Davis. My wife says, ‘Why don’t you say you are a professor?’ I don’t need to say that, but if they ask, we tell, like the Japanese way. If they ask me more, then I will tell them I am a professor.”

Rice: ‘Several colleagues noted that you created a 24-hour Zoom symposium called ‘Taste and Olfaction Around the Globe.’ Seriously, who organizes a 24-hour Zoom?” (The event drew 4000 registrants)

Leal: “I think the best way of describing it is this: in Australia, when the kids are small, they jump in the pool and yell, ‘Dad, help me to swim!’ Right? That’s exactly what I did here. I’m going to do this for 24 hours--then I say, ‘Wait a minute. Does Zoom allow us to stay on 24 hours?’ That’s the first question, right? Then how am I to do this? I cannot stay awake 24 hours. Everything starts to involve me after the idea already is in motion. It’s not like, ‘Let’s plan everything,’ and then boom ! Then I found a very good partner in the United Kingdom, and I found another in Australia. I said, ‘I have this idea, do you want to implement?’ I pick up this eight-hour segment; they pick up an eight-hour segment and the next eight-hour segment. Then we are going to make all these different time zones, and they can participate in their own time zone. Then we record the whole thing and make it available. You know, Zoom creates so many opportunities, and I love this.”

As a teacher, Leal seeks to inspire his students. “There was a particular student that came to me at the end of the course, and he says, ‘I was always not motivated in college, but when I saw you so inspired, then I catch up, and I study so hard now.’ That is why I say teaching is the big payoff, better than the paycheck, you know? That you motivate people.”

Rice: “What do you consider to be your most significant achievement in entomology?”

Leal: “One that comes to mind is the isolation and cloning of the first pheromone-degrading enzymes from the polyphemus moth, Antheraea polyphemus, and the Japanese beetle, Popillia japonica. We demonstrated that these enzymes are crucial for the rapid inactivation of pheromones. We made a cover of PNAS. I am, perhaps justifiably, proud that we have identified why adult mosquitoes are sensitive to the insect repellent DEET. First, we identified the neuron that senses DEET in the antennae and found a receptor. The receptor is named CquiOR136. I am happy that we identified many pheromones that have been applied in agriculture, with tremen- dous monetary and environmental savings. When I identified the sex pheromone of a scarab beetle, Holotrichia parallela, I could not believe these beetles modify amino acid derivates as pheromones. Amino acids are not volatile; pheromones must be. These beetles are clever. Then, another surprise was that the rhythm of sex pheromone release is 48 hours, not circadian! That’s why I love these beetles. These beetles give me so much happiness.”

Murray Blum. The Legends’ article includes an image of Leal sharing a laugh with noted chemical ecologist Murray Blum (1929-2015) of the University of Georgia, recipient of an ESA outstanding award in 1978, and the International Society of Chemical Ecology (ISCE) medal in 1989. Blum’s daughter, Deborah Blum, is a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist (formerly with the Sacramento Bee ), an author, and the director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“The image is from the ISCE meeting in Prague,” Leal recalled. “Murray said that he wished to speak as fast as I do, but he had to pronounce all the words, including verbs and prepositions, so he couldn’t. I rebutted that I don’t speak ‘fast.’ He heard that as ‘slowly.’ We all had a good laugh. Murray always had praise for my work and encouraging words when I was at the beginning of my research career.”

And about his dislike of insects in his early childhood? “I didn’t like insects—the cockroaches and mosquitoes,” Leal told Rice. “Once, a cockroach walked on my lips when I was sleeping. What’s with that? A kid who wakes up in the middle of the night with a cockroach in his mouth? Anyway, this was a bad entomology interaction in the beginning.”

That “bad entomology interaction” is now a distant memory.